This post originally appeared on the “Better Questions” email list. If you’d like to get one email like this a week, please sign up at BetterQuestionsEmail.com. Thanks!

What takes time?

Joseph Roth, the brilliant Austrian journalist and novelist who moved to Berlin in 1920, said at the end of the decade that he could at times no longer distinguish between a cabaret and a crematorium. What was supposed to be amusing made him shudder. Death, correspondingly, could make him laugh.

Modris Eksteins, Solar Dance

Woke up in the middle of the night last night with a premonition of death.

I had gotten vaccinated two days earlier and had spent a long night feverishly tossing and turning.

So maybe it was some residual weariness, my body imagining what might have been if the temperature kept rising.

Or maybe it was my mind engaging in its deep tendency towards irony and reminding me that the shot only protects against one potential source of mortality – and that there are many, many others.

In any case:

Woke up in the middle of the night last night with a premonition of death.

There wasn’t a scene, per se; it wasn’t a premonition of the manner of my death (which would have been useful).

It was simply a full-on, deeply-felt, full-body realization that death is inevitable, and that it is rushing towards me right at this very moment, like I’ve been pushed down a slide and am hurtling towards the earth without the slightest hope of doing anything to slow my fall.

With that as context:

Let’s talk about time.

I wrote last week about how I had decided to experiment with giving up social media.

Partially, that was because I’d been thinking alot about time.

Both how I spend my time…

And how that’s related to how other people spend theirs.

To begin, let us start with the atomic element of my personal social media experience:

The Tweet.

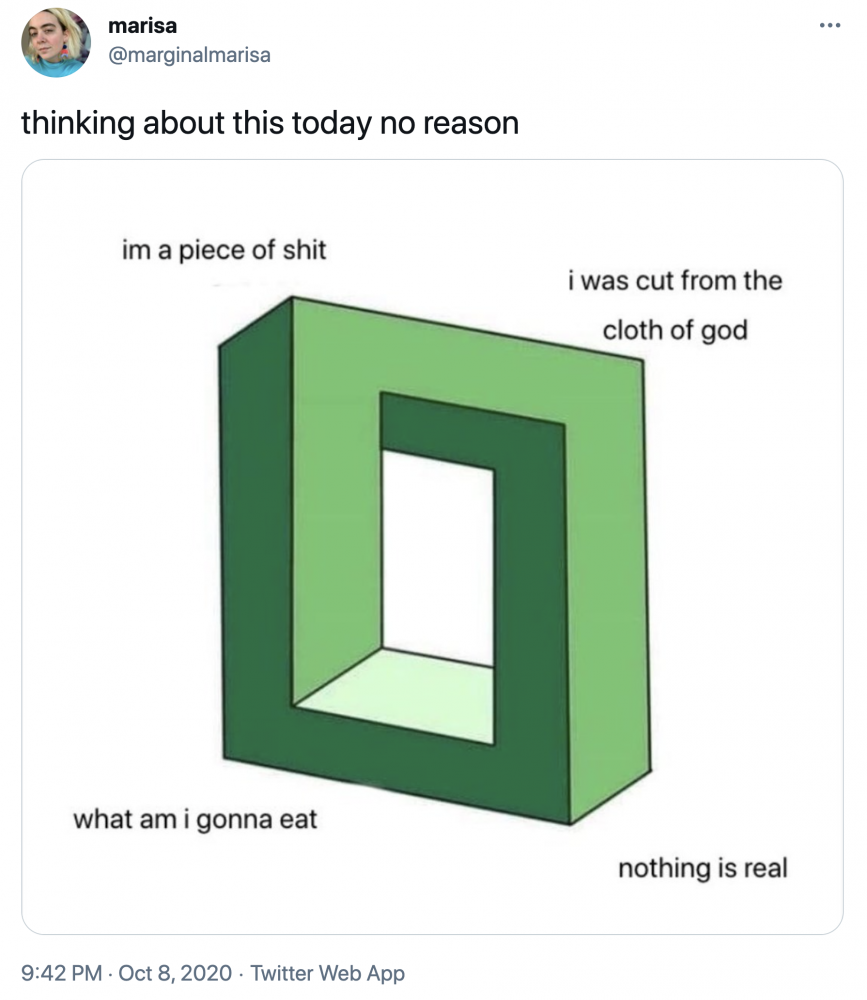

Here is a perfectly great tweet, selected more or less at random from my liked tweets.

It’s funny. It’s got some deeper meaning to it. It’s relatable.

It’s a perfectly bite-sized morsel of a thought. I like it alot.

How much time do you think it took to make it?

And what does that say, if anything, about it’s relative value?

I certainly don’t think that everything that was quick or easy to create is bad, necessarily. I’m sure we can all think of a few.

But everything you consume carries an opportunity cost – while you are consuming that thing, you cannot be consuming something else.

I call this the Haiku Problem.

Why?

I majored in Japanese Language and Literature in college because…well. It was complicated. But I did it.

I vividly remember sitting in a Japanese poetry class, learning about the history of haiku (the famous poetic form that, as Wikipedia descri) “consist of three phrases that contain a kireji, or ‘cutting word’,[1] 17 on (a type of Japanese phoneme) in a 5, 7, 5 pattern, and a kigo, or seasonal reference.”

Our teacher told us that Matsuo Basho, the most famous haiku author, wrote over 1000 haiku in his lifetime.

We pondered this in suitably respectful silence for a moment until a classmate of mine raised his hand.

“If he wrote 1,000 of them,” he asked, “how good could they possibly be?”

There are three ways I’d like you to think about time in regards to what you consume:

- What takes time to create?

- What stands the test of time?

- What lasts the longest of all?

Let’s take a look at these in turn.

- What takes time to create?

Let’s examine the written word as it currently exists.

Say we divide all our written content into a few different categories:

- social media posts

- short articles

- long form articles

- books

(Yes, these divisions are arbitrary and I’m sure I’m missing lots of stuff).

Social media posts generally take the least amount of time to create. You can dash one off in a few moments, or on the toilet.

What would you say are the qualities of this kind of material?

They can be very funny, yes – witty, amusing, relatable.

They can also stir up strong emotions…typically negative ones. Anger is quick to rise up, as is indignation.

Because we can toss them off quickly, we don’t tend to censor ourselves, or to think too hard about the potential consequences. People have had their reputations destroyed (often rightly) by their questionable social media posts.

Compare social media posts with books.

Books, as you will know if you’ve ever tried to write one, are very hard to write.

They take a lot of time. They take a lot of effort. There is editing and re-editing, and then editing again.

Compared to a social media post, it is very hard to accidentally toss something inflammatory off in a book. You have more than enough time to rethink, reconsider, and change your tone.

Correspondingly, the quality of the thought inside the book is significantly higher (on average) than the quality of thought inside a social media post….even when they’re written by the same person!

The ideas inside books undergo a trial by fire; lots of time elapses from the time they are first written down to the time when they are finally released to the world, and that means lots of time to think of revisions. The ideas that end up on the printed page tend to be the strongest version of those ideas that the author can produce, for good or for fill.

Here we see a basic principle emerge:

The longer a piece of culture takes to create, the stronger that piece of culture tends to be.

Not always. But very often.

- What stands the test of time?

Want new ideas?

Read old books.

This is simply a rephrasing of the Lindy Effect. See this wonderful description from the blog post How Substack Became Milquetoast:

“Imagine you’re a book written in 1920. You know that some books become classics while others have a mere flash-in-the-pan success. Naturally, you’d like to know where you fit on the spectrum. But note that survival in this sense is closer to power-law than normal, only a tiny minority of books can endure, least the canon bloat endlessly.

So with each passing day, rather approaching an impending expiration date, you approach the possibility of longevity. Conditional on being alive, it becomes increasingly likely that you are part of the privileged cohort of immortal classics. Paradoxically, the longer you live, the longer you can expect to continue living. This is the Lindy Effect, a kind of near-magical aging-in-reverse enabled by survivorship bias.”

The idea of the Lindy Effect is that the vast majority of cultural works – books, music, films, you name it – fizzle out immediately into nothingness. A very select few will experience fleeting, temporal success…people enjoy them while they’re current and then quickly forget about them.

The “classics,” then – the books and films and songs that have been around forever, have remained culturally relevant, have retained a sense of importance – these are the rarest of the rare. For something to survive over long periods of time, almost by definition, there must be something profound about it.

Of course, simply being profound in some way doesn’t make something good; Mein Kampf certainly had a profound impact on the modern world, but it’s still a pile of dog shit.

But the fact remains that, given a choice between something new and as yet unproven, and something classic that has stood the test of time…you are far more likely to choose wisely by choosing that which is classic.

Again – not always. but very often.

- What lasts the longest of all?

If you adopt, as I’ve been asking of you in this email, the mindset that time is the proving ground of any idea or cultural artifact, where does that lead us?

I would argue that ultimately, we end up here:

We must be unattached to theory, while inclining towards experience.

As Nassim Taleb writes in Antifragile:

“We are built to be dupes for theories. But theories come and go; experience stays. Explanations change all the time, and have changed all the time in history (because of causal opacity, the invisibility of causes) with people involved in the incremental development of ideas thinking they always had a definitive theory; experience remains constant.”

First, it was evil spirits;

Then, it was imbalanced humors;

Now, it’s germs and viruses.

At each stage in that theoretical evolution, the people involved believed that their explanation was the right one.

At each stage in that theoretical evolution, they scoffed at those before them for being so ignorant.

The world’s a complex place; our explanations are never going to perfectly align with the way the world works.

That means a continuous process of creative destruction, of theoretical foundations destroyed, rebuilt, and destroyed again.

Nothing wrong with that – that’s how human knowledge progresses.

But during that entire destructive cycle, experience remained constant.

We all get sick.

We all get old.

We all lie in bed, anxious about dying.

And then, at the moment when we least expect it –

(because we never expect it)

…We die.

The explanations change.

The experience never does.

And so if you want to truly learn about this world of ours –

If you want to see the deep truths of life, and to understand the people around you….

We must be unattached to theory, while inclining towards experience.

Where does all this leave us? This weird-ass email about time?

Here’s the practical take away:

If you’re making a choice about what parts of the culture to consume or engage in…

Try to pick the forms of culture that:

- Take the most time to produce;

- Have stood the test of time;

- Are unattached to theory and inclined towards experience.

And for the no-less-practical, but more philosophically-inclined among you:

Choose well how you spend your time.

We don’t have much left.

Yours,

Dan

Cool Stuff To Read:

A very watchable HBO documentary on Warren Buffett’s life, available in its entirety on YouTube.

I love Buffett, though Charlie Munger, his partner, is my personal hero. I’ve tried to make their philosophy of “doing the simple things well” a guiding force in my life (and have mostly failed, but that’s life).

Leave a Reply