This post originally appeared on the “Better Questions” email list. If you’d like to get one email like this a week, please sign up at BetterQuestionsEmail.com. Thanks!

——

Hi ,

This week, we’re finishing up our series on Behavior Change!

And what treatment of change would be complete without talking about…

Failure.

Am I failing as a hero?

Because of my own background, I am often asked by would-be entrepreneurs seeking escape from life within huge corporate structures: ‘How do I build a small firm for myself?’

The answer seems obvious: buy a very large one and just wait.

How Most Things Fail, Paul Ormerod

Everyone hates to fail.

But we all do it, all the time.

In fact, you are guaranteed to fail, no matter what you do.

If you push past your comfort zone, expand your boundaries, and attempt to do something great…

You wind up in complex, difficult situations…and will eventually fail.

If you don’t push past your comfort zone, do only the bare minimum, and never seek to grow…

Then you are already failing, if only by omission.

No matter how successful you may be, eventually your body will fail. Your organs will shut down one by one, the neurons in your brain will go dark, and the collection of experiences and relationships and beliefs that is “you” will cease to exist.

In case you were unclear on the matter, death remains undefeated.

Living, then, means failing.

The only choice we have is whether we fail while trying to do something great…

…Or fail by simple inaction, passivity, and cowardice.

Our fear is heightened when we encounter the world around us, the world with us, and the world within us. We fear rejection, failure, and mistakes. We are afraid of what others may think of us and, therefore, we are afraid to be ourselves. We are afraid of death and, therefore, we live in fear.

The Psychology of Courage, Julia Yang and Alan Milliren

If failure is universal, why is it so painful?

I can only tell you what I experience:

When I fail, I take it as evidence.

Evidence that I am not enough.

Evidence that I am weak.

Evidence that I lack the strength, or the good looks, or the ability, to do what’s needed.

If only I could follow through…

If only I could focus…

If only I had better genetics…

Each failure seems to prove that I won’t ever be successful.

That I’ll always be unhappy.

That I don’t have what it takes to make it on this strange, hostile planet we live on.

And if I don’t have what it takes, it could all end at any time.

I’m unfit. I’m unwell. I’m not enough.

Failure feels like a death sentence.

Afraid to be myself.

Afraid of death.

Living in fear.

So.

We’re all afraid of death (even if you think you’re not)…

And so we’re all afraid of failure.

But, as I mentioned at the beginning, failure is universal and inevitable.

Our only choice is whether or not we want to fail while trying to do something great.

How do we overcome our fears of failure and move towards what really matters?

By eliminating all-or-nothing thinking.

All-or-nothing thinking is when you believe that you either are or are not.

Your state of being is clear, sharply delineated, and obvious.

You are either successful or unsuccessful.

You are either a failure or not a failure.

Black and white. No gray. No middle-ground.

All-or-nothing thinking is fully a creation of the human mind. There are no straight lines in nature – no clear delineations, no well-marked boundaries. The broader universe doesn’t care at all about how you define one thing vs. another.

Instead, nature is liminal; a smooth transition between states, in constant flux, neither one thing nor the other, but both and neither.

Take the color gradient below

We can all agree that the color changes from orange to read; at the extremes, the differences are clear.

But what about in the middle?

At what point, exactly, does the orange become red?

It must happen. We can all see that it happens.

But it’s impossibly to pinpoint the exact moment at which the change occurs.

That space – the space between states, the mysterious and ineffable and undefinable middle ground – is liminal space.

And while our rational minds, trained on logic and Platonic Ideas, years to define and categorize and split this from that –

Our lives are much more like the liminal space between orange and red than they are anything else.

We are always in flux.

Neither one thing, nor the other –

But both.

And neither.

We’ve been talking about behavior change for a while now.

We started off with Ironic Processes, discussing what happens when we try to “stop” ourselves from thinking “bad thoughts.”

In Dominant Thoughts we explored “priming,” a method for programming our subconscious.

In Sustainably Successful we contrasted maximum achievability and maximum sustainability…and discussed why confusing the two can be so disastrous.

Finally, we discussed Barrett’s Rule: no goals without systems, and went over some of the different systems we can put in place to make change easier.

Throughout each of these essays, I’ve shared my progress as I’ve used these behavior change tactics to help me through a particularly difficult phase of my diet.

I’ve been both cutting calories to shed fat AND changing the types of foods I eat – switching entirely to a low-inflammation diet consisting mostly of ground turkey, chicken, cabbage, cucumbers, blueberries, olive oil, etc.

Doing either one on it’s own would have been difficult; doing them both simultaneously was a big commitment.

How did it go? With all my tools, and techniques, and knowledge…how did I do?

I failed.

I cheated on my diet plan. Not only did I not eat the types of food I was supposed to, I ate nearly 3,000 calories more than I was allowed.

My initial goal was to eat only anti-inflammatory foods for 30 days, after which I was promised higher energy, better focus, a more appealing physique, etc.

I started on April 20th.

I made it to May 5th, about halfway to my goal.

After the high of the junk food wore over, I was pretty despondent.

Not only did I break my commitment to myself and to my nutrition coach, now I would have to go another 30 days before seeing any benefit. I had sabotaged myself and ruined my progress.

This, by the way, is an excellent example of all-or-nothing thinking.

Let’s examine it, for a moment. Is it really true that I had sabotaged my progress? Is it true that I say no benefit?

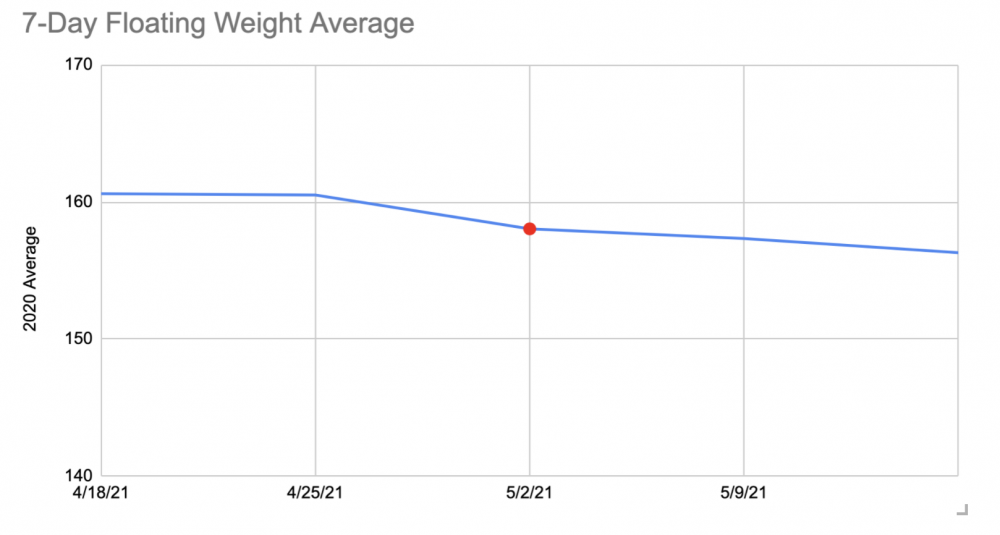

Well, let’s look at my 7-day average weight over this period (the red dot shows the week I cheated):

Not only did I not gain weight that week, I still lost weight – just slightly less than normal.

What about if we look at the bigger picture?

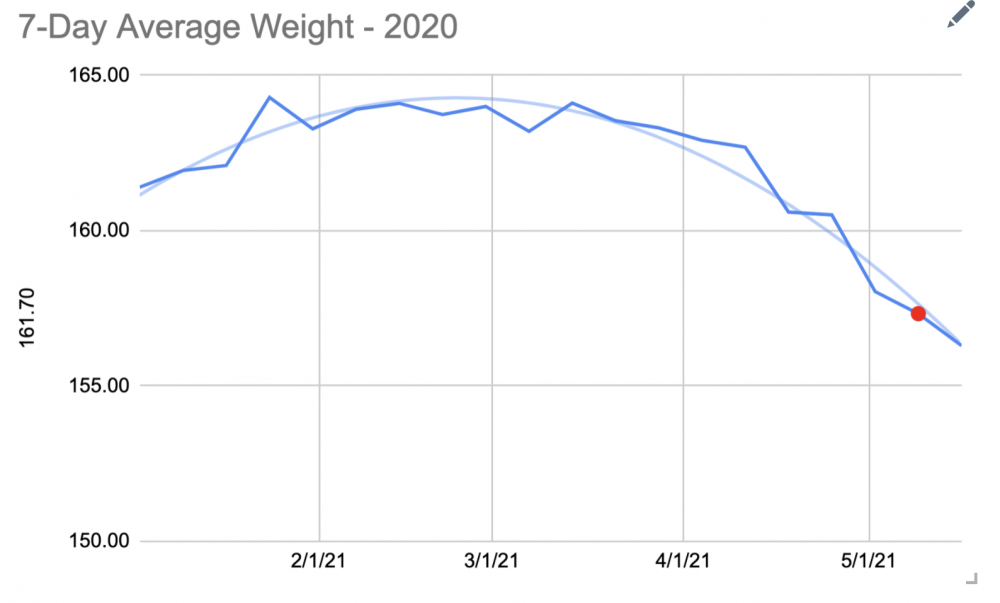

This chart shows my weekly weight trend for the year, with the week of the failure marked in red:

If I hadn’t marked that week in red, would you be able to tell where I had failed?

It seems fairly clear that, regardless of my failure, my overall progress remains more or less the same.

What about the lost benefits of the anti-inflammatory diet? They say that eliminating something from your diet requires a minimum of 28 uninterrupted days to have an effect.

It’s true – I seem to have screwed up that process, and I won’t know what I’d be feeling like if I had stuck to the plan.

But is it true that I received no benefit?

No.

For one, I actually do feel better, and though I’ve had one or two mess-ups, the vast majority of my meals have been 100% anti-inflammatory.

After all, “28 days” isn’t written anywhere in nature. Someone, somewhere, set that as the average length of time required…but it isn’t like absolutely nothing occurs for 28 days, and then WHAM, benefits come rolling in. The process is likely to be a gradual one. That means that I accrued some partial benefits before my failure.

Secondly, there were positive side-effects I hadn’t expected. Eating this special diet required me to prepare my food ahead of time for the week, a process I was really dreading. Once I got going, however, I found it to be relatively painless. Not only that, I saved a ton of money from not eating out, AND discovered that I actually like eating these meals the vast majority of the time. As a result, I plan on continuing to eat only anti-inflammatory foods for breakfast and lunch after my initial experiment is over.

Finally, learning where something breaks is itself useful information. We stress-test bridges for a reason. While I was highly motivated in the beginning, I discovered pretty quickly that eating special meals separate from my family was more of a drag than I anticipated. I missed the social aspects of eating, and found the complete discipline required to be too demanding.

While that sounds like an admission of defeat – and it is, in a way – it was only through that process of trial and error that I discovered what really works for me. I know now that I could easily eat an extremely healthy diet for 2/3 of every day without trouble. I know a lot more about feeding myself in a productive way that also allows me room to relax and enjoy what’s on offer.

And, I look better than I ever have. At 41, that’s something I’m quite proud of.

The point here isn’t to pat myself on the back for eating like an adult.

The point is that my failure, while extremely painful in the moment, had very little practical effect.

All-or-nothing thinking would say that because I fell short of my original goal, I am “a failure” and therefore received no benefit from the work I had put in.

But that isn’t true.

I lost weight.

I felt better.

I learned a lot, both about eating and myself.

While I failed to achieve what I set out to achieve, I ended up much closer to my ultimate goal.

And that is a far more common story among successful people than it might appear.

Remember: if you want to do something great, you’re going to have to push beyond that which makes you comfortable.

You’re going to have to stretch.

To do difficult things.

To confront your fears of rejection, failure, and death.

And ultimately, no matter how hard you struggle…

You’ll fail.

You will fall.

Just like everyone else.

But when you pick yourself back up…dust yourself off, and survey your surroundings…

You’ll find yourself further along than you were before.

A little bit closer.

A little bit wiser.

A little bit better.

Add those failures up over the years…over a life time?

They look a lot like success.

Remember:

You will fail.

But it’s better to fail as a hero…

Than to succeed as coward.

Yours,

Dan.

Cool Stuff To Read:

A great essay on one of the most common ways people self-destruct when trying to get good at something: they mistake long feedback loops for lack of progress.

“Long feedback loops, by their very nature, cannot be pleasurable in the way short feedback loops are. Basically: the thrill will disappear. And that’s okay.”

Leave a Reply